Captured Attention, Captured Democracy

The Habits That Ruin Our Democracy #2

It’s been said that democracy dies in darkness.

But what if democracy dies in the bright, flickering lights of a thousand trivial things?

The greatest threats to democracy may not be in the shadows, but - like a magician’s misdirection - happening center stage, while we’re looking away at something else.

Distraction, and how we’ve come to live with it, is a habit that ruins our democracy.

It’s not the only one. I wrote about the first bad habit - rational inaction - and its antidote - being unreasonable - here.

But distraction is a mighty one: for democracy and for the quality of our lives. Let’s start there.

The quality of your attention is the quality of your life

Our experience of reality is shaped by our attention. We experience a tiny sliver of what’s happening around us; and not just around us: our thoughts, feelings and sensations are subset of a larger potential reality. We know that there’s more out there and in there, but we experience only a part of it.

The psychologist William James described attention as

“the taking possession of the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seems several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalisation, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence. It implies a withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.“

Attention is inherently a process of selection: this is in scope, that is out of scope.

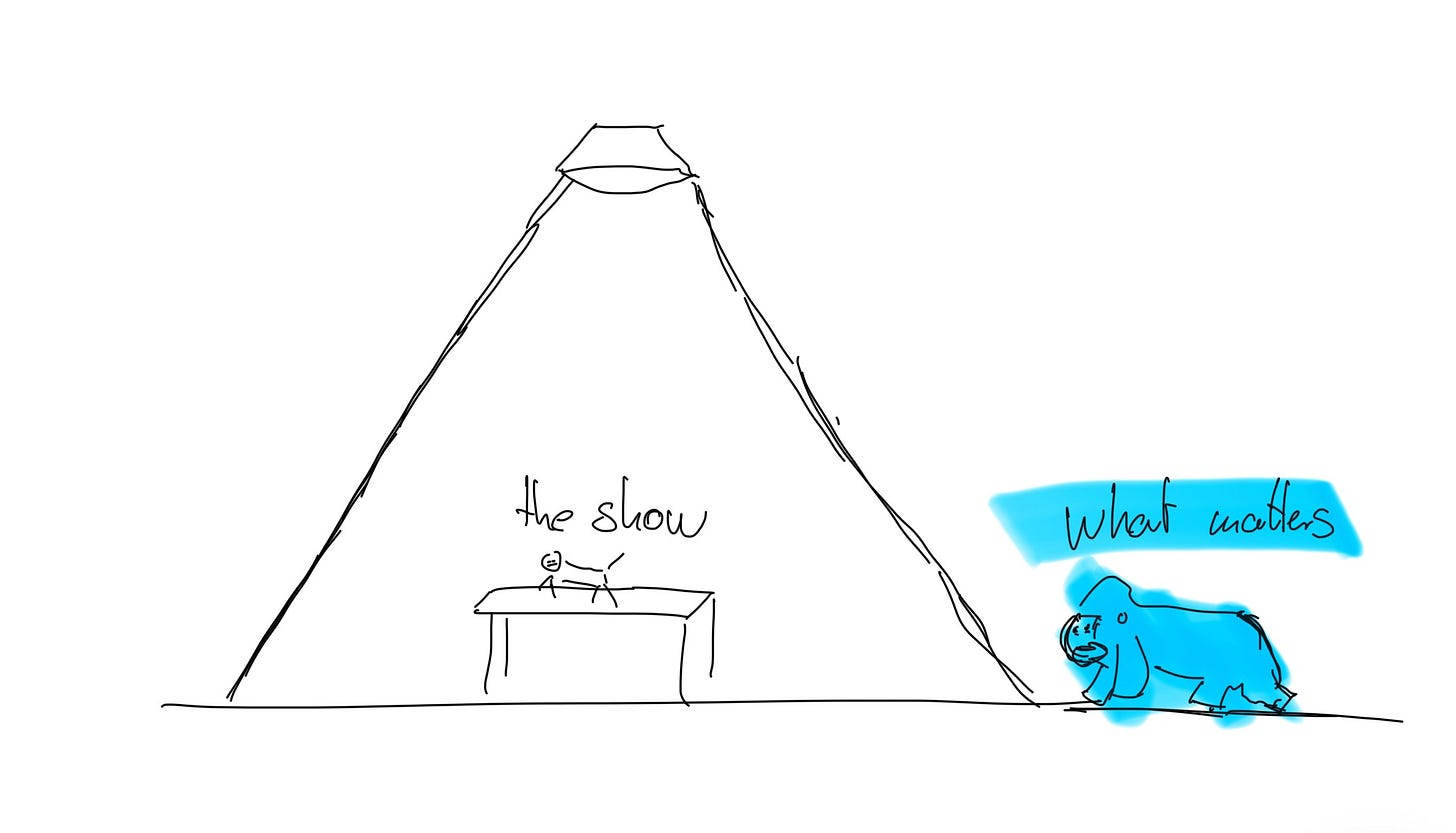

A powerful illustration is the Invisible Gorilla experiment. Psychologists Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons asked participants to watch a short video of people passing basketballs and count the passes made by players in white shirts. Midway through the video, a person in a gorilla suit walks into the frame, beats their chest, and walks off. Roughly half of participants never see it.

It’s not that they are inattentive. They are attentive: to the ‘wrong thing’. Their filter was set to ‘white shirts, ball movement.’ Everything else, including a chest-thumping gorilla, fell outside.

The implication is profound: we construct our experience of reality through where our attention is. What falls outside the filter may still register (the brain processes far more than consciousness accesses) but it doesn’t enter experience. The gorilla leaves a trace somewhere in the visual system. It never becomes your gorilla. For all practical purposes, for all purposes of decision and action, it doesn’t exist.

If attention determines what enters experience, it also distorts how we evaluate what enters. Daniel Kahneman spoke of the “focusing illusion”: whatever we attend to in the moment feels disproportionately important. His formulation:

“Nothing in life is as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it.”

The most striking evidence comes from studies of lottery winners and paraplegics. Conventional intuition says winning millions transforms life for the better; losing the use of your legs devastates it permanently. The data says otherwise. Within a year, lottery winners return to roughly their baseline happiness. Paraplegics, after initial adjustment, report life satisfaction levels comparable to the general population. As Kahneman puts it:

“Everyone is surprised by how happy paraplegics can be, but they are not paraplegic full-time. They do other things. They enjoy their meals, their friends, the newspaper. It has to do with the allocation of attention.”

The lottery winner habituates. The paraplegic adapts. Neither outcome is as important as it seems while you’re thinking about it - and eventually, you stop thinking about it.

Finally, emotion shapes the filter of attention. Psychologist Barbara Fredrickson’s “broaden-and-build” research demonstrates the asymmetry. Positive emotions like curiosity, interest, contentment expand attention. We notice more, consider more options, make more connections. The world opens up.

Negative emotions do the opposite. Fear, anger, anxiety narrow attention to the threat. The evolutionary logic is sound: when a predator approaches, peripheral information is irrelevant. Survival depends on focus. The world shrinks to the object of concern.

The insight is shockingly simple, even if practicing it is not: the quality of your attention is the quality of your life. Direct attention well, and experience improves. Cede control of attention, and you’ve ceded experience itself.

Attention captured

If the quality of your attention is the quality of your life, then captured attention is captured life.

And there’s no shortage of captors, which is where we get to politics.

At their worst, politicians benefit from shifting your focus, from their failure to your outrage, from structural problems to symbolic fights, from what they’re doing to what they’re saying. Political consultant Lynton Crosby called it the “dead cat strategy”: throw a dead cat on the table, and everyone will talk about the dead cat. Not about what you don’t want them to notice

Media benefits too. Attention is the resource and outrage, scandal, and novelty capture it best. Complexity, context, and continuity don’t.

And often political operators and media incentives align. Viktor Orbán’s government ran anti-Soros billboard campaigns and migrant fear-mongering while quietly capturing Hungary’s judiciary. The press covered the provocations. The structural capture proceeded. By the time international observers raised alarms, it was done.

The surface function of distraction is topic displacement: look here, not there. The deeper function is capacity destruction. When your attention is perpetually captured, you become less used to directing it.

Negative emotion further accelerates this. Fear and anger narrow attention which is evolutionarily useful when facing a predator, but democratically catastrophic when facing complexity. The result is a permanent narrowing: citizens locked onto whatever triggered the last emotional spike, incapable of sustained focus on deliberating what actually matters.

Withdrawal

The rational response to an impossible environment is withdrawal.

Attention researchers find the average person switches tasks every three minutes; recovering focus takes twenty-three. The math doesn’t work. Sustained engagement with complex issues becomes structurally impossible. So people withdraw from issues that don’t concern them directly. But while withdrawal feels like reclaiming control, it’s surrender.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi observed that

“what you pay attention to is not just an individual issue, but a social one.”

He was talking about family life, and how it takes active work - paying attention - to make it work. But the insight applies broadly to politics. When citizens withdraw their attention, the field clears and those who manufactured the overload face no opposition.

The antidote: sovereign focus

If captured attention is captured life, the antidote must be taking charge of where your attention goes.

Sovereignty, in the political sense, means self-determination: a people’s right to govern themselves without external control. Sovereign focus is the same principle applied inward: the capacity to direct your own attention, rather than having it directed by those who profit from capturing it.

This means designing conditions where attention serves your priorities, not someone else’s.

That takes work at four levels:

1) Define the main thing

You can’t protect what you haven’t named. What actually matters to you, not what’s urgent, but what you’d regret neglecting in five years?

Because most people haven’t answered this clearly, their attention defaults to whatever shows up next.

Write it down. Not vaguely, but specifically. Define your life areas. Then define your priorities across life areas. Your 90-day goals. The non-negotiables. If it’s not explicit, it’s typically unclear and even if it’s clear, it’s easily pushed to the side by life’s ups and downs.

2) Own the main thing

Clarity without execution is wishful thinking. Ownership means building systems that translate priorities into consistent action.

This operates at multiple horizons. Yearly: what would make this year successful? Monthly: what milestones matter? Weekly: what moves the needle? Daily: what gets protected time today?

The key is structure, not effort. Goals written down. Time blocked. Boundaries set. A weekly review that forces honest accounting: did my time match my stated priorities?

And remove triggers. The phone on your desk. The browser tabs. The notifications. The workday punctured by meetings. Each is an invitation to capture. Audit your environment: how well is it designed for focus?

3) Reset to the main thing

You will drift. Everyone does. The practice is noticing and returning, quickly.

Build reset rhythms. A pause between meetings: what matters now? A daily review: where did I drift? A breath before opening the phone: what am I looking for?

4) Extend the main thing

Here’s where it becomes more than personal: becoming someone others look to for focus. And acting responsibly in that role. This changes how you operate:

How you structure your day signals to others what deserves attention

How you respond to requests for your time teaches others what’s important

How you shape a meeting agenda determines whether it drifts or delivers

How you shift conversation when it turns trivial models a different standard

Where you spend time on social media...

T.S. Eliot wrote the famous lines

“This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

Hannah Arendt warned that political evil emerges from thoughtlessness and passivity.

Democracy doesn’t require constant attention from everyone on everything. But it requires sustained attention from enough people on enough issues they deem important to create accountability.

The alternative has to involve taking charge of your focus.

p.s. on that note, in March I’m running a 4-week sprint to build the pillars of personal focus: clarity on what matters, systems to act on it, ability to re-focus when you drift. Together with peers who keep you accountable. If you’re interested, find out more and join the waitlist here.