My two lessons on focus as a new dad

Also relevant for non-parents

I became a dad a couple of months ago. As much as I was looking forward to her birth, I’ve not just had the typical concerns: would her mother and the baby be alright and healthy, how would we cope as parents and partners, could I live up to my expectations of being a good dad.

I cannot deny that I was also concerned about what work would look like for me in the future. Especially: would I ever be able to focus on my work again? It sounds silly writing these words. But with everything I’ve worked out for myself, helped clients with and written about focus (see a list of my favourites below), that really was a worry in the back of my mind.

Behind that question, there were three subtle beliefs:

I won’t be able to focus (properly) on anything other than the baby

If I try to focus I’ll get distracted

Everything will be different

But I was wrong. I want to share why and how, because I think it’s relevant not just to parents but to anyone committed to the focused life. Here’s what I’ve learnt (and when I say ‘learnt’, it’s more: re-learnt, experienced, became aware of).

Lesson 1: Time pressure compressed work to its essentials

I thought my work sessions would become fragmented disasters with a baby. A few minutes here and there, how could I create anything meaningful from that? I knew of the value of undistracted, deep work. I had experienced flow moments regularly, if not every day, then at least a couple of times a week. Now, this seemed out of reach.

But as it turned out, I was wrong.

Instead, when I found the time to work, I became more focused and effective. Whether during a 45-minute nap or the 2-hour window while my partner took the baby for a stroll, I had a set amount of time - and needed to make the most of it.

Timeboxing is a classic productivity tool: you allocate a fixed amount of time to a specific activity in advance; you don’t work on a task until it’s finished, you work e.g. 30 minutes on it and then stop.

The reason this works is summed up in Parkinson’s Law: work expands to fill the time available for its completion. (A fun side note: Parkinson, a historian, used it in a humorous way to explain why Britain increased the number of its civil servants in the Colonial Office while the empire was in decline; he also used to explain why ‘an elderly lady’ may spend a whole day writing and sending a postcard where busier people would complete the task in a few minutes.)

So, when you limit the time available, you compress work to its essentials. Now, for me, timeboxing isn’t so abstract anymore, it’s very concrete: it’s my daughter waking up. But the lesson is there for anyone: constraints on your time are a gift forcing you to prioritize and focus. If you don’t have a baby imposing those constraints, impose them on yourself.

But I do think there’s a difference between setting a timer, and a baby crying for attention: pressure.

How often have I timeboxed in the past, knowing very well that, really, I had more time than I artificially imposed on myself. Real pressure, in the right dose, makes the difference.

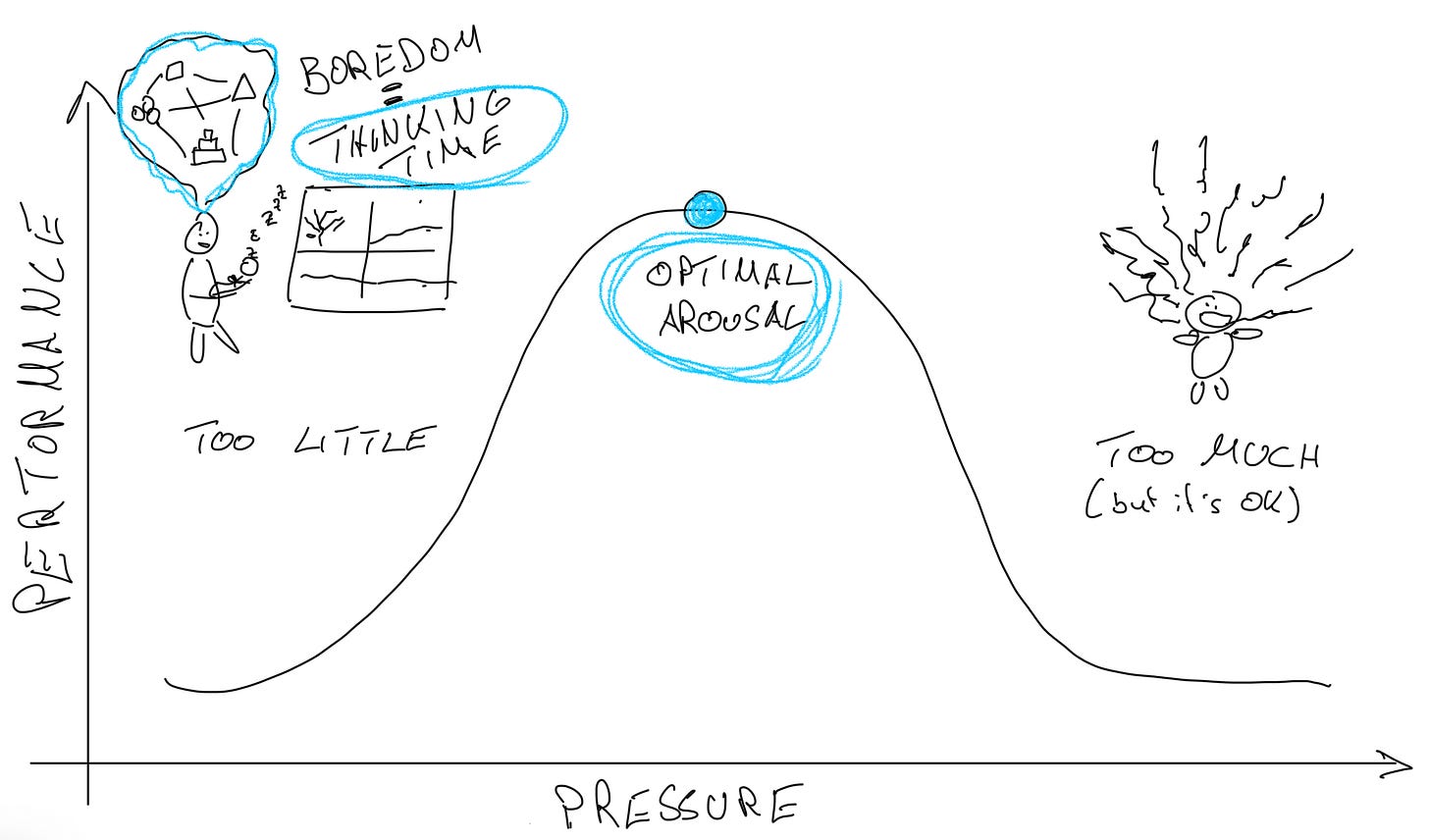

Psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson discovered that performance follows an inverted U-curve with pressure: too little and you’re bored (’under-aroused’); too much and you’re in distress and freeze (’over-aroused’). But at the ‘optimal arousal zone’ somewhere in the middle, pressure is ‘eustress’, positive stress. It feels like alertness, a state of being ready to go.

I knew this time away from my daughter mattered, and I wanted to be there when she came back. That’s just the right amount of pressure to make my work time count.

So set limits that create positive stress:

Tell a colleague or client exactly when you will deliver your work. Why it works: public commitment creates a psychological cost for failing to follow through.

Schedule your hardest task for the 60 minutes right before a meeting. Why it works: incidental deadlines increase the perceived difficulty and importance of a task.

Make a commitment to a colleague, linked to a penalty if not following through, like donating to a political cause you despise. Why it works: we’re wired to feel the loss of pain more strongly than the joy of a gain.

Lesson 2: Boredom became thinking time again

If you’re old enough to remember: waiting in line meant waiting in line, not catching up on email or scrolling on social media. Sitting in a doctor’s waiting room meant avoiding awkward eye contact with other patients. Being early to meet someone and just... standing there.

We called it boredom. Now these moments are mostly extinct, and we lost something we didn’t know we needed. It turns out that boredom was cognitive composting. What looks (and smells) like waste, is - with time! - the breeding ground for something new.

Neuroscience backs this up. When we are focused on goal-directed tasks, the Task-Positive Network is in charge: excellent for execution, but terrible for original connection. It is only when the brain is ‘idle’ that it switches into the Default Mode Network (DMN). It looks like time ‘off’, but really it’s a state of incubation where the brain scans your library of knowledge to link ideas that your focused mind would consider unrelated.

What looks like doing nothing has long been part of intellectual work.

Charles Darwin constructed a gravel path at his home in Kent he called his ‘thinking path’. Every day, he strolled its loops, keeping a pile of stones and kicking one away with each turn. His son said the walks were for ‘hard thinking’: not analyzing data, but letting his idle mind wander and metabolize lots of (seemingly unrelated) data. It was here, walking for years, that he developed the theory of evolution.

The songwriter and creator of the hit musical ‘Hamilton’, Lin-Manuel Miranda, had his breakthrough while floating in a pool in Mexico. With no scripts or distractions, his DMN took over. He later said: “The moment my brain got a moment’s rest, Hamilton walked into it.”

The trap for modern knowledge workers is believing that sitting at the desk is where the work happens. In reality, the desk is often where you process the work, but away from the desk (or looking out of the window) is where you generate novel work. Darwin’s path and Miranda’s pool remove the stimulus which allows the brain the bandwidth it needs to turn ‘compost’ into something new.

My daughter, by falling asleep on me, pinned me in place, often without a phone and only the window as entertainment. She, surely unaware of it, returned something I’d lost. Boredom gave me thinking time.

How to reclaim boredom without a sleepy baby to trap you?

Protect transition moments: the walk to the office, the wait for coffee, the minutes before a meeting starts.

Create constraints: no phone in the bedroom or at your desk during deep work. No podcast on a walk.

Separate processing from generating. When you’re stuck on a problem, stop working on it. Do something undemanding (shower, walk, stare out of the window) and let the incubation do its work.

There’s no need for a baby to apply these lessons (there are other good reasons to have a baby).

You need real stakes on your time and genuine emptiness in your downtime. Most productivity advice gets this backwards by adding tools, filling gaps, extending hours. The focused life is more about subtraction: fewer fake deadlines, less performative busyness, more intervals where nothing needs to be done.

I’ve come to see constraints and boredom not as obstacles to focus, but as part of how focus works.

Like this? Subscribe to get a 5-minute assessment for your personal focus profile + weekly tools

Take a look at my favourite focus articles: