The Case for Being Unreasonable

The Habits That Ruin Our Democracy #1

I used to think bad politics was mostly about leaders making bad decisions.

Then, I noticed something that is not easy to admit.

Some patterns I disliked in public life were showing up in my own daily behaviour. Not in any dramatic form like shouting matches, throwing around insults, or calling for (political) violence. At least not that I’m aware of.

But they did happen in small ways, in ways that were much easier for me to brush off. Moments where I stayed silent because I assumed someone else would speak. Times I let outrage and the hilarious pull me away from what mattered. Days where I slipped into my own bubble and avoided reaching out. And plenty of situations where I grabbed the easy explanation instead of doing the harder thinking.

Individually, none of these moments look harmful.

But when I zoomed out, they formed a pattern.

And that pattern looked a lot like the dynamics we see at scale in politics:

Inaction

Isolation

Distraction

Shallow thinking.

Sometimes, you see something and cannot unsee it.

For me, that was true for these four patterns. These patterns show up quietly in all of us, now and then. Multiply these behaviors with millions of people repeating them daily, and they create - or at the very least enable - the politics we’ve ended up with.

In this post, let me focus on the first of these problems.

Bad habit #1: rational inaction

Every election season, you hear the same excuse: ‘My vote doesn’t matter.’

In a narrow sense, it doesn’t. The chance that your single vote decides an election is vanishingly small. Staying home is the rational choice.

Except... if everyone thinks this, and does this. When everyone acts rationally as an individual, we all lose.

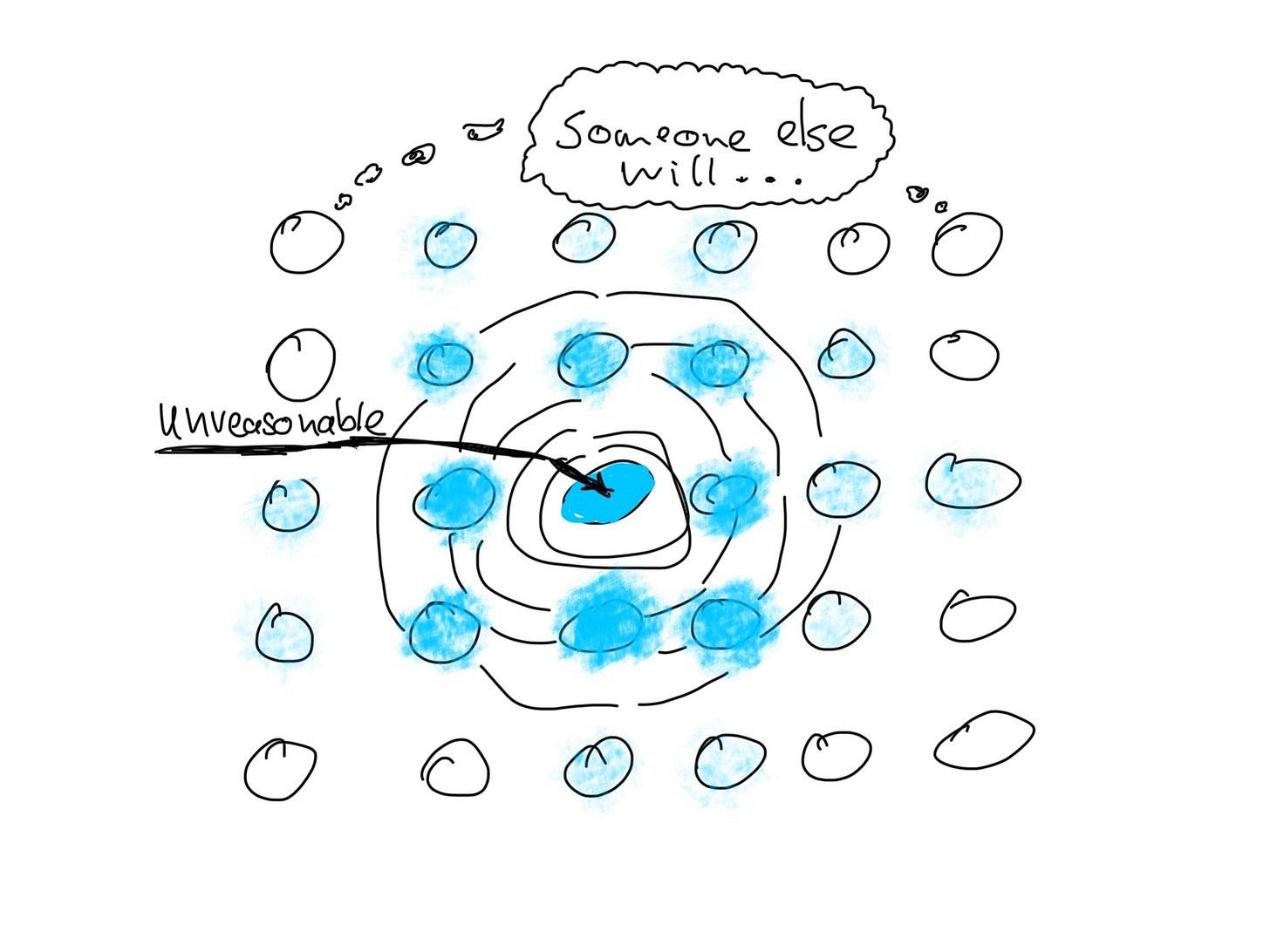

This is the collective action problem, and it goes beyond voting. It shows up every time we tell ourselves: someone else will handle it. Someone will speak up in that meeting. Someone will call out the lie. Someone will organize the protest. Someone will donate. Someone will run for office.

Each individual calculation makes sense - for a while at least. But collectively they’re stupid: they lead us to worse outcomes than anyone actually wants.

Most people do not wake up hoping for lower trust, more corruption, or politics dominated by the loudest fringes. Most people don’t want institutions that feel distant, brittle and captured. Yet, this is exactly what rational inaction produces.

This isn’t a result of active calculation or malice. Rather, we fall for a mental shortcut that tells us the ‘crowd’ has things under control.

Democracy’s bystanders

Psychologists call this diffusion of responsibility. The more people who could act, the less any one person feels the weight to act. In emergencies, bystanders freeze because they assume someone else has already called for help. In democracies, citizens disengage because they assume someone else is doing the work.

The numbers are brutal. If you are one of a million voters, the likelihood that your vote ends up being decisive approaches zero. If you are one of ten people in a room watching injustice, it may feel like your responsibility is 10%. The math incentivizes inaction.

But here is what the math misses: humans are mimetic beings. We copy each other. Not just behaviours but beliefs about what behaviours are possible.

When you act, you do not just add one unit of action to the world. You change the calculation for everyone watching. This could reinforce the problem of rational inaction: if people around me act like this, I also should or maybe even want to act like this.

But it could also be how we begin to solve the problem.

Starting before it makes sense

Your neighbour sees you knock on doors and thinks: maybe I could do that. Your colleague sees you speak up and thinks: maybe next time I can say something. Your friend sees you show up and thinks: maybe showing up is what people like us do.

Social scientists call this the three degrees of influence. Your behaviour ripples outward, affecting not just the people you know, but the people they know, and the people they know. You are not one in a million. You are a node in a network, and nodes have leverage.

Consider how every political shift in history started. Not with millions acting simultaneously, but with small clusters who refused to wait for the crowd. The math said they were irrational. Well... maybe you need to be irrational for large-scale change to start.

George Bernard Shaw put it best:

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man”.

There is a trick from emergency response that applies here. When someone collapses in a crowd, you do not yell “Someone help!” You point at a specific person and say: “You, in the blue shirt, call 112.” You make it personal. You collapse the diffusion.

The same principle works for civic action. Abstract appeals to citizens bounce off: “Go vote”, “This time is different”, “Our democracy needs you”. I don’t know about you, but they don’t catch me, and in my experience they bounce off, even if people nod politely.

But direct asks to specific people can land.

“I need you to come to this meeting on Thursday” can become a commitment and the basis for more:

When responsibility is personal, diffusion evaporates. When the ask is specific, calculation shifts from “what difference does one person make?” to “what happens if I let this person down?”.

If someone shows up once, the psychological barrier drops. They’ve proven to themselves it’s possible. They’ve seen how the system works. They’ve become the kind of person who does this.

And the person who showed up because you asked becomes the person who asks someone else. Diffusion of responsibility reverses into diffusion of agency. Your - seemingly irrational! - initial choice to act despite negligible direct impact cascades into collective momentum that retroactively justifies itself.

On that note: That reversal - from diffusion of responsibility to diffusion of agency - is what I’m trying to create in a small peer group starting in March: four weeks to build a personal focus system that actually holds. If you’re curious, I’m sharing more at the end of the article.

Influence beats control

The antidote to rational inaction is a different frame of rationality. One that accounts for influence, not just control. One that counts second-order effects, not just first-order impact. You control very little directly. Your vote is one in millions. Your voice is one in billions.

But you can influence much. Every choice you make sends a signal about what choices are available and desirable. Every action you take (re-)defines what seems possible for others. Every time you break the bystander pattern, you make it easier for others to break it too.

The question is not: will my action solve the problem?

The question is: what kind of person do I want others to see when they look at me?

p.s. I believe the same logic applies to personal focus: you control very little directly. But you can influence your environment, your systems, your defaults. That’s the premise of the program I’m running in March. It’s a 4-week sprint to build the pillars of personal focus: Clarity on what matters. Systems to act on it. Ability to re-focus when you drift. And with peers who keep you accountable. If you’re interested, find out more and join the waitlist here.