The Focused Generalist

Why "Pick One Thing" Is the Wrong Advice for the Right Problem

I’ve spent years coaching people on focus. I write about it, I’ve built a system around it. And for most of that time, I carried around what felt like a contradiction - one I didn’t want to look at too closely.

I’m a generalist.

I coach executives, design and deliver teaming workshops, have a consulting background but also a PhD in political science, I’m an organizer and activist, write a newsletter (and a lot about focus!) and read across disciplines…

When I sit down to “pick one thing” - which is the advice I’ve heard a hundred times - something in me resists. Part of that resistance is a recognition that the advice doesn’t fit.

For a long time, I treated that resistance as a discipline problem. Maybe I just wasn’t serious enough. Maybe real focus required a kind of amputation I wasn’t up for. I suspect I’m not alone in this.

The guilt nobody talks about

If you’re a generalist, you know the feeling. You’ve read the books. You’ve seen the case studies of people who went deep on one thing for a decade and emerged as masters. You understand, intellectually, that focus matters. And every time you try to narrow down, it feels like putting on a shoe that’s two sizes too small.

So you oscillate. You commit to one thing, last three weeks, then switch to another or revert back to taking pride in being a generalist - and add “lack of focus” to your list of personal failings.

Here’s what I think: the problem isn’t necessarily your discipline (though it can be). The problem can be that you’re applying a specialist’s tool to a generalist’s life. And that’s a category error, not a character flaw.

Two types of generalist worth separating

Not all generalists are the same. Here’s a distinction I’ve come to find essential, and it’s uncomfortable because it doesn’t let you off the hook.

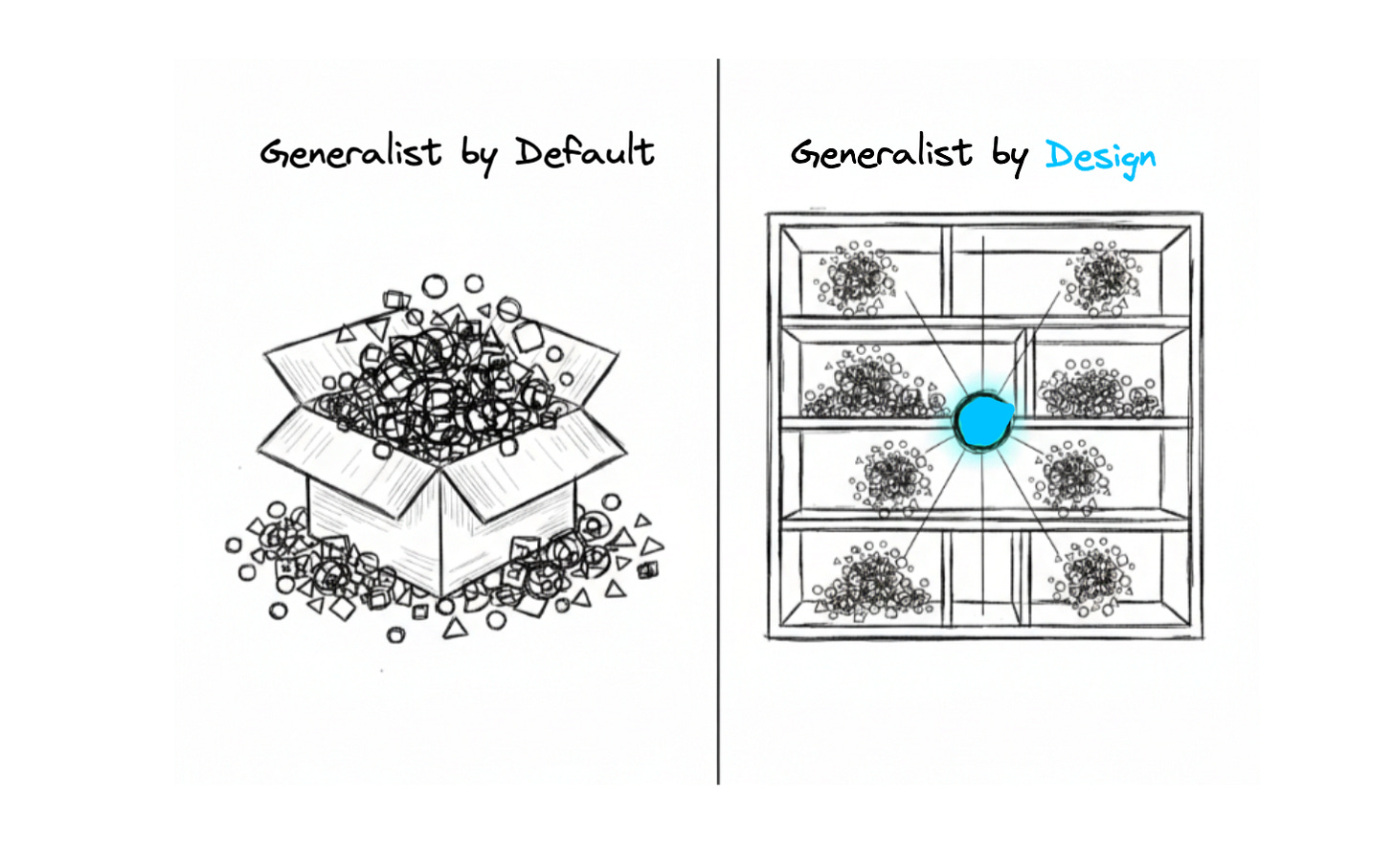

Some people are generalists by design. Their breadth serves a thesis. They know what they stand for, what they refuse to become, and their varied interests come together into a coherent whole that they actively manage. That’s the focused generalist.

Others are generalists by default. Their breadth is a symptom. It comes from avoiding commitment, from fear that choosing means losing, or from a lack of clarity so deep that everything looks equally worthwhile.

The honest question: which one are you? Because the rest of this article is about becoming the former. And becoming the former requires confronting the possibility that you might currently be the latter.

Focus isn’t one thing

Here’s what changed how I think about this. Focus has four distinct capacities, not one:

Clarity: knowing what matters. Your values, your direction, what you refuse to tolerate.

Ownership: acting on what matters consistently. Systems, boundaries, planning — the infrastructure that turns intention into behavior.

Reset: recovering when you drift. Everyone drifts. The question isn’t so much whether you do, it’s how quickly you notice and return.

Extend: multiplying focus through others. Leading in a way that makes the people around you more focused, not more dependent.

It’s the CORE focus method I’ve written about before (and I’ve developed a quick diagnostic that shows how sharp your focus is on each dimension).

And here’s the insight that matters for generalists: the conventional focus advice - say “no” more, block your calendar, time-box your tasks - lives entirely at the Ownership level. It’s about what you do and how to do it more consistently. And for specialists, that’s often enough, because their Clarity is already settled. They know what they’re about; they just need to protect the time.

For generalists, the problem sits one level upstream. You can’t consistently act on what matters most when you don’t know what that is. Ownership without Clarity is just effective wandering. And no amount of productivity advice will substitute for the foundational work of knowing what your “investment thesis” actually is.

This is why generalists feel guilty when they try conventional focus advice. They’re applying an Ownership tool to a Clarity problem. It’s like rebalancing a portfolio when you haven’t decided what you’re investing for.

The moment I understood this, the guilt dissolved.

Now, the question became: is my breadth chaotic or coherent?

The life portfolio

And it’s here where the analogy of portfolio thinking is helpful.

A diversified investment portfolio can be focused - if it has an investment thesis, i.e. a set of convictions about where value will come from. The positions are varied, but they’re varied for reasons. And the portfolio gets rebalanced periodically because conditions change and allocation needs to follow.

Your life’s focus works in a similar way.

Your investment thesis is your foundational focus — the values, commitments, and refusals that define what you’re building toward.

Your positions are your activities, projects, roles, and interests.

Your allocation decisions are how you distribute energy and time across positions.

Your risk constraints are your anti-vision, what you refuse to become, the outcomes you’re actively hedging against.

What sets a focused generalist apart isn’t having fewer interests than a “generalist by default”. They have a thesis that makes their breadth coherent. Each position connects to the thesis. New opportunities get evaluated against it. The question isn’t “should I do fewer things?” but “does this position belong in my portfolio?”

This is different from having a mission statement. Mission statements tend to be aspirational and vague: “make an impact,” “live with purpose.” An investment thesis includes what you refuse. It includes allocation logic and proportion. How much of your energy goes to which position, and why?

When you can’t find your thesis: start with what you refuse

If you’re reading this and thinking, “Great, but I don’t have a thesis”, that’s OK. Positive vision is hard to formulate. I struggled to articulate mine, and it took time (but well worth it!).

What helped me get unstuck was starting from the other end. Not “what do I want?” but “who do I refuse to become?”

The anti-vision was immediately clear. I could name the regrets I refuse to have, the compromises I refuse to make, the versions of success that would feel empty. And those refusals, that negative vision, turned out to be a sharper portrait of my values than any aspirational statement I’d written.

Daniel Pink’s research on regret points in the same direction: our deepest regrets cluster around inaction on things we knew mattered. The regrets you refuse to have are a direct map to what you actually value.

So if a positive vision, or thesis, feels out of reach, start with the anti-vision. What you refuse to tolerate is often more honest, and more actionable, than what you aspire to build.

The coherence test

A portfolio without rebalancing is just a collection. And most generalists never rebalance, they only accumulate. New interests layer on top of old ones. Commitments expand but never contract. The thesis, if it exists, gets buried under activity.

Here’s the test I keep coming back to:

If someone studied how I spend my time, could they reverse-engineer my thesis?

This is a harder question than it sounds. Not “do I have a thesis?”; most thoughtful people can articulate one if pressed. The question is whether your thesis is legible in your behaviour. Whether an outsider, looking only at your calendar, your energy, your actual choices over the past month, could reconstruct what you claim to stand for.

If they couldn’t, i.e. if your behaviour tells a different story than your thesis, then you don’t have a thesis. You have a narrative. And a narrative you don’t live by is just self-mythology.

That’s the diagnostic.

The practice is gentler: every couple of weeks, I ask myself: What deserves more of me right now — and what has been getting more than it deserves?

No dramatic reallocation or existential reckoning. Just an honest look. I like that “more of me” is deliberately broad: it could mean time, creative energy, emotional investment, or simply attention. And “more than it deserves” isn’t a general judgment of worth for any one of my activities. It’s a judgment of its weight relative to the thesis, right now.

The diagnostic keeps you honest. The question keeps you moving forward. Together, they replace “I should narrow down” with something a portfolio manager would recognize: evaluate, allocate, rebalance.

The pull remains

I want to be honest about what this doesn’t solve - at least it hasn’t for me. A portfolio frame won’t eliminate the pull of breadth. You’ll still feel the tug of a fascinating new domain, the temptation to start something that doesn’t fit the thesis, and maybe the nagging sense that you should be more like the specialist who went deep.

The difference is that you have something to evaluate against. You can feel the pull and ask: is this a new position worth adding, or is this a distraction resembling an opportunity?

It doesn’t make you a specialist. It makes you a strategist: someone whose breadth is deliberate, whose variety has a thesis, whose portfolio gets managed instead of accumulated. In short, a focused generalist.

The question that didn’t help was “how do I do fewer things?”

The more useful question is: “what’s my investment thesis — and does my portfolio reflect it?”