The One Thing You Know (But Aren't Doing)

A 7-day experiment to act on what you know

I have two questions for you:

What’s one thing you know that if you did it well and you did it consistently, it would make a significant positive difference in your life?

Why aren’t you doing it?

At first glance, question one looks easy. Many of us already know the answer. We’ve carried it around in the back of our minds for months, maybe years.

But here’s the twist: some of us think we know - until we try to write it down. That’s when the fuzziness shows up. Is it really this one thing, or that? Does the wording capture what I actually mean, or just what sounds right?

So here’s how I see it:

If question one comes easily, the real challenge is turning knowing into doing.

If question one feels fuzzy, the challenge is seeing more clearly in the first place (and doing can help with that, too)

A 7-day experiment

Either way, the best next step is the same: turn it into an experiment.

For the next 7 days, do three things each evening:

Write down what your 'one thing' is

Write down what you did about it

Write down what helped or got in the way.

That’s it. No big goals, no heroic declarations. Just track it with a few sentences.

This little experiment makes the invisible visible.

Clarity through repetition

If question one feels fuzzy, the experiment gives you more clarity through repetition.

Each evening, when you sit down to write your “one thing,” don’t worry if it shifts. In fact, that’s the point. On day one it might be “exercise.” On day two, “call my parents.” On day three, “eat better.”

Instead of proving you don’t know, this shows you how clarity emerges. Writing it down is like clearing condensation from a mirror: the more often you wipe, the sharper the image gets.

Over a week, you’ll notice patterns. Some answers repeat, others disappear. You may discover that what felt like ten different “one things” is really one theme in disguise.

Why aren't you doing it?

And if your answer does come easily, the challenge shifts to question two:

Why aren't you doing it?

Once you track your answers, the obstacles start to reveal themselves.

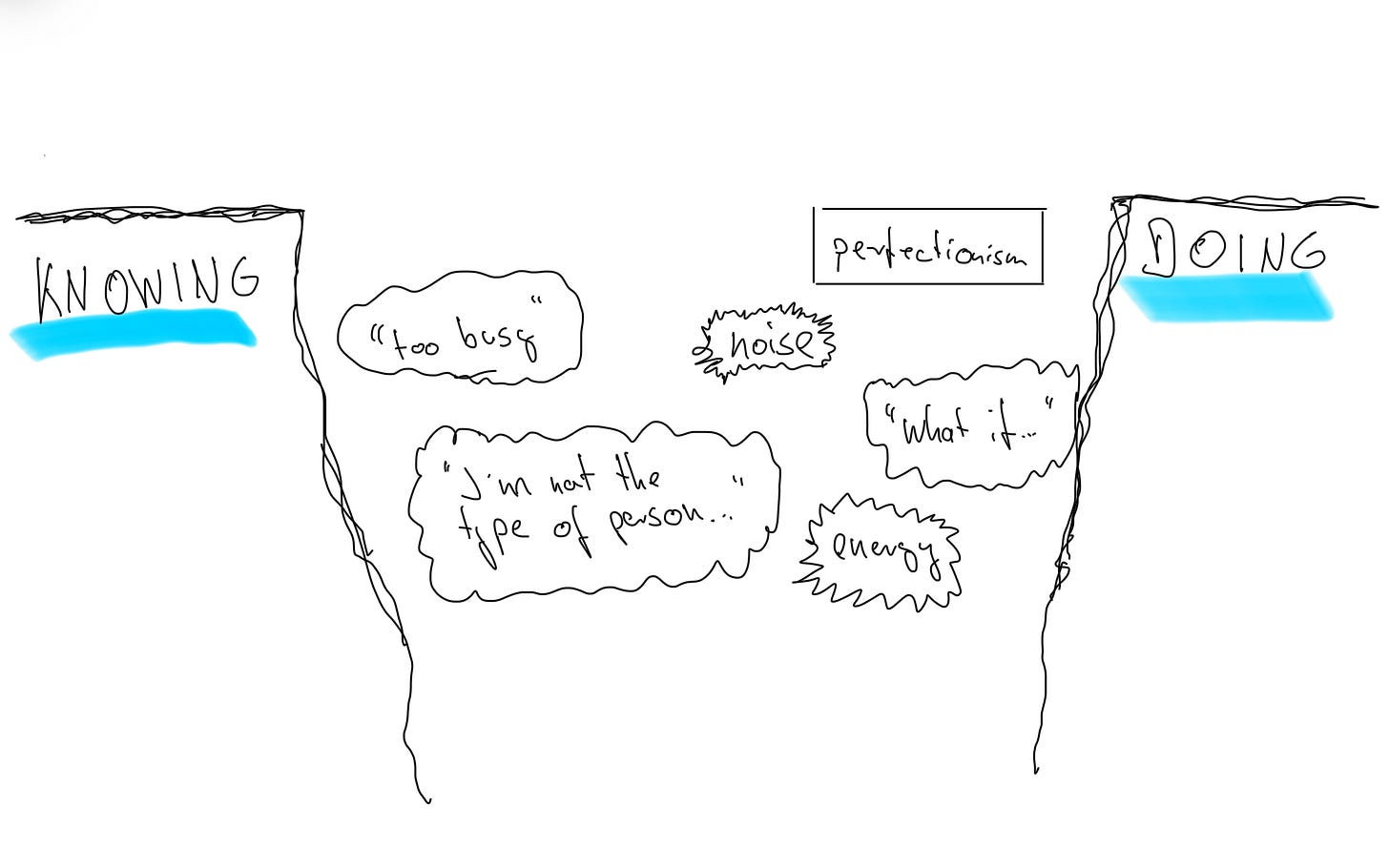

These are the usual suspects I’ve heard most often:

Time: “I’m too busy.”

Energy: “I’m exhausted by the end of the day.”

Fear: “If I try and fail, I’ll feel worse.”

Ego/identity: “I know it’s important, but I don’t see myself as the type of person who does that.”

Noise: “Other people’s demands crowd it out.”

Disapproval: "What will my colleagues think."

Perfectionism: “I don’t want to start until I know I can do it.”

Some are external: noise, time, other people. Some are internal: fear, ego, perfectionism. The tricky part is we often misdiagnose the problem. We say “I don’t have time,” when what we really don’t have is courage. Or we say “I need more energy,” when what we really need is being OK with doing less.

So before you rush to fix the surface-level problem, notice: which obstacle feels most familiar to you?

This week in my own clarity experiment, I noticed two suspects sneaking in.

There were two things I knew would make a real difference: one in my relationships, the other in my work. Simple, clear, obvious.

And yet I didn’t do them consistently.

Why? Two suspects made themselves known.

In my relationships, it was time. I kept telling myself I was “too busy.” The days filled up with tasks, and what I cared about most got the leftovers. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to show up, it was that I hadn’t protected the time.

In my work, the suspect was more subtle: ego, with a dose of fear of disapproval. I noticed hesitation as soon as I sat down to do the 'one thing'. What if (potential) partners pushed back? What if I only heard crickets after submitting my proposal? Behind the hesitation wasn’t lack of clarity, but fear of judgment.

At first, I told myself I just needed more discipline. To try harder, to force it. But that wasn’t it. What I needed was to spot which suspect was standing in the way. That alone is worth a lot: you can point to it and that takes some of its power away. And once you see it, you can design ways to make it harder for the suspect to get in.

Clarity is simple, but not easy.

We think we know what matters, but we don't really.

We think about what matters, but don't feel it.

We know what matters, but don't act on it.

We believe we need more discipline, but what we really need is to spot the suspects.

The experiment is a way to notice all this. To put the answer on paper, to see the patterns, to name what’s really in the way.

Once you can see it, you can face it. And once you face it, you can change it.